Native hunting and trapping methods

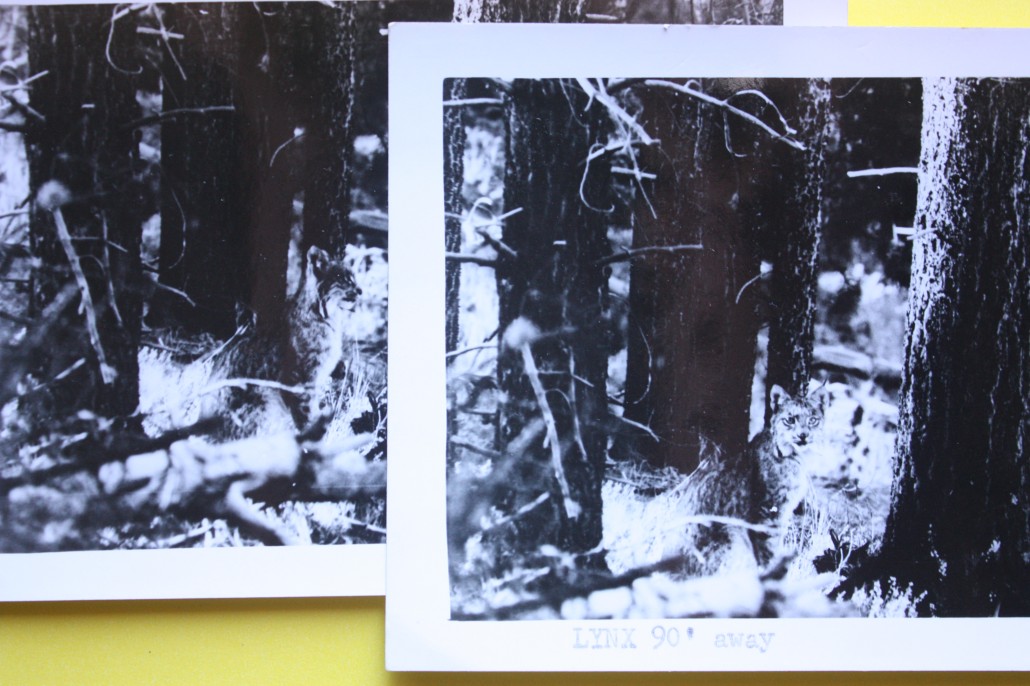

Can you see him? Two old photographs of a lynx (ca. early 1960) watching us from the bush, somewhere in British Columbia. Photo taken by Elton Alexander Anderson, grandson of Alexander Caulfield Anderson

I told you quite some time ago, that I could write about the Native methods of trapping the many wild animals in the wilderness that surrounded the fur trade posts in Northwestern British Columbia, or New Caledonia. This information comes from the writings of Alexander Caulfield Anderson, fur trader, now settled in what is now North Saanich. He writes to encourage and inform the new settlers into the territory, and so while he writes the history of the Natives in New Caledonia and their hunting methods, he also advises new settlers on what animals there may be here, and how to deal with them. We begin immediately, with the bears:

“There are three varieties of Bears in British Columbia — the Black, the Brown, and the Grizzly (Ursus Ferox). The two former occupy the low lands throughout — they are timid, and comparatively harmless. The extent of their depredations consists, where the country is close and woody, in the occasional abstraction of a stray pig from the settler’s stock. With the aid of dogs they are readily treed, and then easily shot; or they may be stalked like the deer. Some caution requires to be used in attacking the female when suckling her young; her maternal sympathies then rendering her at times rather troublesome.

“The Grizzly Bear is larger than either of the other two varieties, and one does well not to attack it unless pretty certain of his shot. This bear is a fierce antagonist when molested though rarely venting its rage at other times unless when suddenly surprised. It does not possess the same facility for climbing trees as the others. Its flesh, too, is tougher and comparatively of inferior quality. It is more gregarious too: and when found in squads of several together has to be treated with caution. The skin of this Bear, like that of the others, when in its prime is valuable…

“The Ta-cully [Dakelh] have various ways of hunting the Bear. At most seasons with dogs and the gun; but in the fall, when the passes along the river banks are fairly traced, very successfully with strong snares of twisted thongs of Rein-deer hide, parceled round the noose with the bark of the Dwarf Birch so as to avert suspicion of danger. The snare is fastened to the small end of a heavy spare of pine, pivoted at one third of the distance from the point where the noose is attached — the outer and heavier end is supported by a couple of stakes tied together at the top, and planted so loosely as to be disengaged by the first struggle of the capture bear. The heavy end, thus allowed to descend, with its great power of leverage, completes the process of strangulation.

“There are two varieties of Lynx found in British Columbia — the spotted (Lynx Maculata) and the Grey (L. Argentea) — the former confined to the lower and maritime districts, the latter frequenting the upper country. They are captured with short snares of strong cord, placed in a kind of trap or entrance way, established at the foot of a large pine tree — the bait, a piece of salmon or a fragment of venison. The Grey variety has a beautiful fur, and in this respect greatly excels the other. These animals appear and disappear at intervals, simultaneously throughout the Indian Country. they will sometimes continue for several years constantly increasing in numbers; and then suddenly disappear, leaving only a tithe of their number behind from which the race is regenerated. An epidemic disease showing itself in an external eruption, is the prelude to their disappearance, death ensuing as in the human species when attacked by the small pox in its most virulent form.

“The Pine Marten (Mustela Martes) frequents the wooded and mountainous tracts, of the interior chiefly. Like the Lynx it disappears partially at intervals, and then reappears in great numbers, probably affected by similar causes. Falling-traps of wood, baited with a fragment of salmon, are employed to catch them. The fur is valuable.

“The Wolverine (Taxus Gulo) is found in the wooded districts, chiefly in the vicinity of the Mountainous ridges. It is a mischievous animal, despoiling the hunter’s traps of their captured prey, and not unfrequently breaking into caches, if not strongly secured. Though not a large animal, its strength is great. In common with the Lynx it lies in ambush for the Rein and other Deer; which, once seized, either of them readily destroys.

“The Common American Otter (Lutra Canadensis) is commonly found among the small lakes, and sedgy stream-beds. It is hunted with the gun, or caught with steel traps set by the water’s edge in its accustomed tracks.

“The Fox is found of three varieties — the Red, the Grey or Cross Fox, and the Silver Black. The second is simply a cross between the two others. Its skin is next in value to that of the Silver Fox, whose fur is very highly esteemed, both for its extreme beauty and its comparative rarity. The Fox is caught with the ordinary spring trap: in the setting of which some dexterity and many precautions are necessary, in order successfully to entrap this wary animal.

“There are several other fur-bearing animals to which it is not necessary specially to advert — except the Beaver, which I shall presently notice.

“The Common Hare of the North (Lepus Variabilis) appears periodically during several years in immense and constantly increasing numbers. then, like the Lynx which preys upon it, it suddenly becomes scarce, thinned off by in like manner by an eruptive epidemic. the failure of the Hare generally (or I may say always) precedes that of the Lynx by a year; and I have thought it more than probable that the disease was generated in the latter through preying on the diseased remains of the former. Previous to the appearance of the fatal epidemic I have mentioned, the Hare affords an important source of livelihood to the natives and European residents. The natives fatten them in this way — selecting a convenient grove of young firs (P. Banksiana) they cut a great number of the juicy saplings down. Leaving it for a fortnight or three weeks, the whole grove is traced with hare-paths in the snow. the hares, abundantly supplied with the food which they prefer, have by this time become very fat. Springs are set in all directions, and vast numbers are thus captured nightly. Each family selects its own range or beat for snaring. In traveling during winter the voyageurs frequently help themselves from the snares when the owner is not present, depositing a piece of tobacco or other trifle in exchange. The shooting of the hare on the snow-shoe is an excellent sport, requiring, however, a sharp eye and a quick finger on the trigger. As its name implies this hare varies its color with the seasons. In summer it is of a tawny grey, in winter white; the alterations of color taking place gradually with the approach of spring and autumn.

“The Moose, or American Elk, (Orignal of the French) (Cervus Alces) is not found in the Lower and Middle Districts. There are a few between Fort George and Bear’s Lake, and more rarely a stray animal wanders as far Westward as Chinlac and Fraser’s Lake, near both which places they are occasionally, but very rarely, killed. It is not, however, till we approach the Rocky Mountains that their territory may be said fairly to commence. the horns of this animal are palmated like those of the fossil Elk of Europe. Its great size, and the surpassing delicacy of its flesh, render it a highly valued prize of the chase. It is solitary in its habits, and extremely wary; so that to become a successful moose-stalker is a height of hunting ambition to which every one does not readily attain.

“I have, however, nearly exhausted my catalogue of those quadrupeds which may tempt the ardor of the adventurous sportsman in British Columbia. I may mention at the same time, that the Wood-buffalo is found about the heads of Peace River, and between that vicinity and the Tate Jaune’s Cache… It resembles in every respect the Bison of the Saskatchewan plains, but is of larger size, and less gregarious, probably on account of the nature of the country it inhabits. When fully alarmed the Mountain-buffalo, like the Caribou, makes off to a great distance fairly “crushing the forest in its race” until its alarm subsides.

“And now for the Beaver. In attempting to describe some of the habits of this animal, I cannot do better than have recourse once more to note, penned when I was very young, and now referred to useful at a maturer age. The partial extracts that I may give must be supposed as being addressed familiarly to an inquisitive friend.

By the bye: what be your notion of a Beaver-lodge? The question seems so simple that one feels almost disposed to apologize while putting it. Judging, however, from my own misconceptions of some years back, and again from the marvelous accounts one sees constantly blazoned to the World in print, it may not be amiss to dwell awhile on the subject. For instance, I very recently saw in a work, professedly for the instruction of youth, a plate, supposed to represent a group of Beaver-lodges. Nice little mud cottages with neatly rounded roofs, and accurately vaulted doors, seated on a pretty eminence and shared by palms and other trees of tropical vegetation. the following astounding revelation accompanies the print. “This vignette represents the Beaver, with several huts of three stories high, built on the edge of a clear stream, supported and shaded by tall trees and brambles. The huts have usually two doors, one to the water, and one to the land.” [Guy’s Pocket Encyclopedia: London, 1832]. And to complete the picture a veritable beaver, perhaps intended to represent the “oldest inhabitant,” is gravely promenading in the foreground! What can your old and esteemed friend, the worthy Mr. Wombwell, say after this? — His vocation’s gone, Hal, depend on’t; the philosophers have usurped it!

“Seriously, however; the Beaver is a semi-amphibious animal: it requires a dry station for its resting place while securing frequent access to the pool which it instinctively creates by damming, and at the bottom of which its winter-store of provisions is deposited. The lodge itself is merely a large collection of poles and sticks disposed like a hollow cone, with earth and mud outside in which bushes and weeds speedily take root and flourish. The entrance is from beneath the water which covers the lower part of the lodge, while the upper and habitable stages are dry. Here amid soft hay and other bedding the inmates warmly nestle; taking only an occasional plunge to visit their magazines of poplar and other succulent woods, therefrom to abstract a portion for breakfast or for dinner. If alarmed in the ledge, they at once forsake it; escaping through the holes at the bottom, and swimming beneath the surface to the covered ways excavated in the banks of the Beaver-tarn, accessible from beneath the surface, while having a small orifice from inland to admit air for respiration…

“There are several methods of taking the Beaver. That most in vogue during the season of open water is the steel trap. The mode of setting it is sufficiently simple, but a good deal of tact is necessary in the selection of its position. It is placed in shallow water at such a depth that the beaver in swimming over it shall touch the “palette,” or trigger, with its paw. The trap is fastened with a chain about six feet in length, attached to a stout picket driven into the bottom at the edge of adjacent deep water. Once caught, the beaver in its struggles to escape, reaches the deep pool beyond and is sunk by the weight of the trap. .. the lure by which the beaver is attracted towards the trap is the Castoreum. A small portion is rubbed upon a twig planted close by the trap. towards this the beaver, if near, eagerly swims, to soon come in contact with the hidden danger which seals his doom.

“In winter the Beaver is captured by means sometimes of Nets formed of Babiche (thin, hardened thongs of deer-hide) the meshes several inches square. Holes are first cautiously made in the ice, about twenty feet apart with an ice-chisel or “trench” (Fr. Tranche from trancher, to cut). The ends of the net are then passed from one hole to another by means of a long pole bloated beneath the ice; and stretched by means of stones attached to the lower corners. The lodge is then disturbed; and the inmates swimming eagerly towards their refuges before described are entangled and captured. I will not, however, enter more deeply into this mode of hunting, some of the subsequent details of which are albeit very interesting.”

Excerpts from: Alexander Caulfield Anderson, “British Columbia,” Draft unpublished Manuscript, Mss. 559, BCA

Notes: Anderson often talked of the ingenuity of the Dakelh hunters who he admired, and it seems that they were quite inventive, as this post shows. Mr. Wombwell, mentioned above, had a menagerie in London in the 1820’s. Almost certainly, young Alexander Anderson visited it. I suspect the phrase that follows immediately afterward comes from Charles Dickens. Anderson read and enjoyed the Pickwick Papers and other Dickens writings.

Castoreum is a gummy product comes from the scent gland of the beaver, and it was collected by the fur traders and shipped to London for perfumes and various medical uses. It is used even today for perfumes, I understand.

Copyright, Nancy Marguerite Anderson, 2014. All rights reserved.